From medieval times up until the end of the Edo Period (1868), it was customary, at least in the upper echelons of society, for a widow to become a nun after the death of her spouse.

A Nunnery Founded by the Widow of a Kamakura Regent

Thus was Tokeiji founded by Kakusan-ni in 1285, a year after the untimely passing of her husband, Hojo Tokimune, eighth regent of the Kamakura Period, at the young age of 34. You might remember Tokimune as the popular leader who commanded the Japanese forces to victory against the Mongol invasions of 1274 and 1281.

Tokeiji was founded and dedicated to the regent's memory, with his son, Hojo Sadataki, appointed as the first chief priest.

Kakusan-ni established the temple as a refuge and sanctuary for wives who had been mistreated or abused by their husbands. A three-year stay at the temple, later reduced to two, earned the women the right to be considered officially divorced.

Men Barred From Entry for More Than 600 Years

Tokeiji is the only survivor of a group of five nunneries (amagozan) established by the Hojo family as the female counterpart of the five monasteries known as Kamakura Gozan. It remained a nunnery for almost 600 years, headed solely by women. In fact, men were barred from the premises. This practice was rigidly enforced all the way until 1902 when the last abbess was replaced by a man, in the same year that Tokeiji was placed under the jurisdiction of Engakuji Temple, a few hundred meters across the valley.

The last recorded “divorce” at the temple took place in 1871, three years after the Meiji Restoration ended the Tokugawa shogunate, curtailing the power of the samurai or warrior class and vastly diminishing the role of Buddhism in national affairs. Henceforth, Shinto was proclaimed as the state religion, with the emperor anointed as the divine figurehead and absolute ruler.

Divorce in Ancient Times Not Easy for Women

One might think that divorce in ancient Japan was a civil right that was ahead of its time, but upon closer scrutiny, you will see that it did not apply to women as well as to men. During the Kamakura Period, husbands need only write a formal letter of divorce (mikudarihan) consisting of three and a half lines to dissolve their marriage, without even having to give any reason why. They might divorce their wives for not producing a child or for the plain, simple fact that they had found another woman that was more to their liking.

Conversely, women were required to spend two to three years at Tokeiji before they were granted a divorce from their abusive husbands. But, at least they had such a recourse, and over the years Tokeiji became a sanctuary and a home for women who wished to break free from the male-dominated society that had remained in place in Japan from ancient times.

A Refuge That Attracted Daughters of the Elite

Thus did Tokeiji attract daughters of the ruling elite to seek admittance to the secure confines of the nunnery. One such was the fifth abbess, Yodo-ni, daughter of Emperor Go-Daigo (1288-1339) and older sister of Prince Morinaga (1308-1335). Another was Tenshuni, granddaughter of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the second great unifier of Japan. At eight years of age, the hapless girl was personally entrusted to the temple by Tokugawa Ieyasu, founder of the Edo Shogunate, who, incidentally, had decimated her family at the siege of Osaka Castle in 1615.

Powerful and greatly revered in its heyday, Tokeiji stands unique among Kamakura's temples and shrines, and is still known today as the Divorce Temple.

Resting Place for Numerous Illuminaries

Small though it is, Tokeiji is well worth a visit. It is a typical mountain temple built into a valley, with an approach up stone steps and a cemetery at the back, the resting place of several luminaries, including Dr. D.T. Suzuki, the famous Zen master, writer, and thinker, side by side with his good friend and collaborator, British-born Reginald H. Blyth, personal tutor to then Prince Akihito and later eminent translator of classical haiku. Suzuki and Blyth were instrumental in introducing and promoting awareness of Zen Buddhism and haiku poetry in the West in the 1960s.

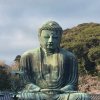

Within the grounds there is a bell tower at the entrance, a couple of teahouses, a small museum of Buddhist art treasures, and the main worship hall that enshrines a statue of Shaka Nyorai, the historical Buddha, seated in lotus position.

A Temple in Which to Be Rather Than to See

I have often thought on my several visits to Tokeiji that it is not so much a temple to see as one in which to “be” in the literal sense of the word. There is something about the gentle rustling of the trees in the late afternoon, the moss-covered paths and stone steps, the fragrance and beauty of the flowering plants, and the air of reverence around the well-tended graves that imparts on the visitor a singular sense of serenity and quiet contemplation. It's as if you slip away to another time and place, eons removed from contemporary city life, inducing a soothing state of spiritual reflection and renewal.

Tokeiji is good to visit along with Engakuji, Joichiji, and Meigetsui-in, all within easy walking distance of JR Kita Kamakura Station.

Getting there

Tokeiji Temple is 300 meters and 5minutes walk from Kita Kamakura Station on the JR Yokosuka Line. For access, please take the West Exit of the station.

More info

Find out more about Tokeiji Temple.